Why should content strategists care about the Semantic Web?

“The moment you launch a website, you’re a publisher,” wrote Kristina Halvorson in the first edition of her trailblazing book “Content Strategy for the Web” (Halvorson, 2009, p. 20). This statement not only emphasizes the importance of following web content good publishing practices but also underlines our responsibility as content strategists to populate the Web with good content.

Content is not written in a vacuum. The second you hit publish on a piece of content, you add it to the ever-expanding repository of human knowledge. It’s up to us to write content that adds another valuable layer to the existing related data and fits into the mental models of our audience, who will be typing into the search bar.

This is exactly the message of Amerland’s book - semantic search is a technology created to go beyond the simple act of information retrieval by interpreting the searcher’s intent and by expanding the results with suggestions and opportunities for serendipitous discovery (Singhal, 2012). It’s been built to elevate useful information above online clutter (the noise, as David describes it in Chapter 7 on social media marketing and search) and outright spam.

Google, the world’s most popular search engine capturing around 91% of the search market share across all devices (Statista, 2024), pioneered technologies that created an unrivalled search experience. It only made sense that the concept of semantic search is taught in the context of the incredible journey that Google’s search algorithm has gone through to shape how we search today (Kopp, 2022).

Introduction Chapter 1: What Is Semantic Search? Chapter 2: What Is the Knowledge Graph? Chapter 3: What Is New in SEO? Chapter 4: Trust and Author Rank Chapter 5: What Is TrustRank? Chapter 6: How Content Became Marketing Chapter 7: Social Media Marketing and Semantic Search Chapter 8: There Is No Longer a “First” Page of Google Chapter 9: The Spread of Influence and Semantic Search Chapter 10: Entity Extraction and the Semantic Web Chapter 11: The Four Vs of Semantic Search Chapter 12: How Search Became Invisible Bibliography |

Table 1. Table of contents of “Google Semantic Search: Search Engine Optimization (SEO) Techniques That Get Your Company More Traffic” by David Amerland.

What is semantic search? #

In David’s words (Amerland, 2013, p. 6), semantic search is “the transition from a “dumb” search of single web pages that have a probabilistic value of containing the information we are looking for to an intelligent search that delivers real answers or leads us to the very answer we are looking for on a web page that has nothing to do with the search query we used and therefore would not have come up in the traditional keyword-activated results of the past.”

Why is semantic search better? Simply put, it removes ambiguity, decreases the possibility of search results inaccuracies, and taps into the existing ocean of data to pull out the most relevant information for that one particular instance of search. Semantic search is personalised and trained to our preferences by how we interact with information on the web. This makes search engines something much more - a prediction engine.

To understand semantic search, we have to look to the father of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee (The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), 2023). In his Scientific American article published in 2021, Tim painted a vision of the Web as an interconnected library of data linked together in a meaning-rich way, making it possible for computers to interpret data similarly to how a human does (Berners-Lee et al., 2021). He called it “the Semantic Web” relating the concept to semantics, the study of linguistic meaning (‘Semantics’, 2024).

The Semantic Web holds the promise of an intelligent search agent that can access, parse, and derive meaning from the co-created Web of data and the connections between data. For semantic search to become a reality, everyone who contributes to it uses structured data that gives machines the information they need to interpret the rich meaning behind words on the pages. For a regular webizen, this means having the ability to type into the Google search engine bar such an ambiguous query as “best ice cream” and receive an answer that has taken into consideration:

- the intent (“wanting to eat ice cream”);

- the location of the searcher;

- their past search history and activity, which indicates preferences and tastes;

- a list of local ice cream places in the form of a Google Maps list called Local Pack (Ahrefs, 2022);

- reviews and opinions from other ice cream enthusiasts on the internet;

- rankings from reputable ice cream authorities such as travel portals, culinary magazines, or local media publishers;

- relevancy of the information (sources that indicate content freshness will be prioritised);

- and related searches that the user might want to action next.

“Semantic search is all about creating connections in a world where point A is actively looking for point B and vice versa.”

David Amerland goes deeper into explaining the technology that makes semantic search work. Built upon the existing search infrastructure of spiders (web crawlers or search engine bots), a database (or index), and a large network of computers that stores, semantic search needs three main ingredients to operate. They are a Universal Resource Identifier (URI), a Resource Description Framework (RDF), and an ontology library. The URI is the name of the resource, which is then refined by an RDF, “a set of rules that allows the transportation (or translation) of data from one database, where the URIs are stored, to another without loss of meaning or a mix-up of value” (Amerland, 2013, p. 12).

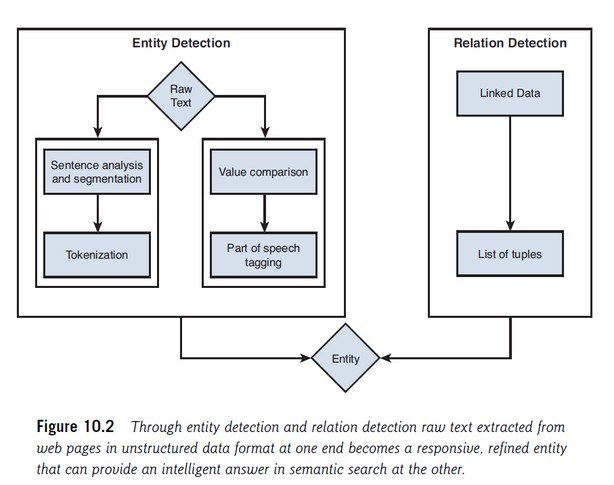

The ontologies are where the intricate relationships and ambiguities are resolved. Ontologies are “maps of entities and their collections” (Steele, 2024), that computers reference when processing data. An entity “describes the essence or identity of a concrete or abstract object of being” (Kopp, 2022). In semantic search, it can be an object, a person, a brand, or a romantic movie. Entities and how they come to be are the subject of Chapter 10, where Amerland goes into technical details of how Google creates entities through a process called Entity Extraction and enriches them with meaning through user-submitted metadata or signals derived from how the entity is interacted with on the web.

It’s important to add that understanding the technical side of semantic search is not a prerequisite for creating content that performs well on Google. David assures the reader that the most important elements of creating valuable content are very much aligned with the principles of content strategy. These are:

- Understanding your business,

- understanding your audience,

- and understanding the context within which the audience reaches out for the type of content you provide.

To ground semantic search in how it can help the business, each chapter ends with a set of questions anyone responsible for publishing on the web should ask themselves to tap into the opportunities offered by semantic search. These are “back to basics” and very much non-technical, related to the why, how, and what of a business - the questions any company needs to be able to answer.

Using the Knowledge Graph in your content strategy #

In Chapters 2 and 3, David Amerland makes a case for thinking of your business's online presence as one entity that is fragmented and contained within multiple platforms.

Google’s semantic search is powered by Knowledge Graph (Singhal, 2012) a knowledge base that is best visualised as a virtual web of answers that is fed by information submitted through a variety of online presence services - websites, social media, professional networks, profiles, databases, and Google Search itself. Fragmentation is inevitable because the modern Web landscape is built on online services that guard and contain data. Search itself is fragmented, with different platforms, services, input methods or appliances calling for different approaches to search optimisation (David writes more about it in Chapter 8).

However, this doesn’t prevent Google from attempting to put together your company’s online presence - regardless of the data silos and no standards on data interoperability (Amazon Web Services, Inc., 2024) - through its Knowledge Graph technology. This might sound ominous but what Google is doing is asking for transparency of your data, activities, and connections on behalf of its users.

“In semantic search, the goal is to map the interaction of relationships between people and websites across the Web. The belief is that signals have an inherent meaning, and if a sufficient breadth and depth of captured data is mapped we will end up with a scalable, ever-evolving picture of connections across the Web that will allow a search engine to understand the true meaning of a word through its associated connections.”

How is content strategy related to the Knowledge Graph?

The best way to approach the synergy between the content you want to create and how it will feature on the internet is to dive deep into the research of the existing connections before you put the virtual pen to paper. Content strategists need to learn to love the Knowledge Graph, a visualisation of the data that already exists on the internet (Better Content, 2020), as a portal through which they can identify the existing conversations. All that is required of them is to add the next node and join the thread.

The job of semantic search, any search really, is to provide answers to its users. We as content strategists need to be aware that whether we are mindful of it or not, our online footprint is indexed and enriched by Google to create an online calling card reflected in the Knowledge Graph. Amerland points out that in the past, what came up in search could be manipulated by the crowd of skilled SEOs acting on behalf of companies wielding large budgets. A company could reach the profitable top-ranking spot on the search engine results page through a targeted SEO campaign that heaped sponsored praise and customer reviews studded with keywords and anchor links, which Google used to translate as reputation points. Today, the ability to build a wholesome online presence reflected in Google’s semantic search ultimately goes back to the topic of trust, reputation, and authority. It is no longer possible to influence search by black hat SEO techniques (WordStream, 2009) because search engine optimisation evolved beyond counting the number of keywords or backlinks - the latter known as PageRank, the first ranking algorithm by Google. Today the system of ranking signals is complex and closely linked to the quality of content seen primarily through the lens of user experience (Search Engine Journal, 2023).

Modern SEO is focused on what Google calls E-E-A-T: experience, expertise, authoritativeness, and trustworthiness (Google, 2024a). For better or for worse, E-E-A-T cannot be simulated or artificially created because, in 2024, Google’s semantic search is beyond old-school search engine-first content tactics. The key to excelling at search engine optimisation is content that answers real problems. Already in 2013, when David published his book, the quality of content was at the centre of his advice

“Key to all this, driving all the activity, is content. Content marketing has become so vital to all aspects of search engine optimization in the Semantic Web that it underpins many of the activities that your business or brand needs to engage in.”

Building trust in your brand through semantic search #

Building trust online may appear an even more difficult task now than it was in 2013. Queue the generative AI revolution, misinformation, and the global crisis of trust (Edelman, 2024).

However, fear not because companies that consistently invest in user-centric content strategy will still come on top when it comes to semantic search (although the success of master semantic search might look different from company to company - see Chapter 8 for more insights). Chapters 4 and 5 explain the importance of establishing trustworthiness through strategic online identity building using the examples of Trust and Author Rank. Both concepts have slowly lost their significance as Google continued to work on sophisticated algorithms and natural language processing models capable of recognising website trustworthiness and authority through complex quality assessment calculations rather than assigning numerical values to links, keywords, or citations. I still recommend reading the two chapters as they paint an interesting picture of Google’s evolution, including the painful demise of Google + (University of Washington, 2023).

What is still relevant is the overall impact of strategic online presence management where a company finetunes its connections and asserts its position within a domain, the space in which that organization operates (Fitzgerald, 2022). This is reflected in the company’s editorial calendar which builds authority; the social media strategy which increases engagement; and collaborations with relevant topic experts and influencers (Chapter 9), which further strengthen online authority by association.

By occupying a space within a topic and actively building a stream of content that comprehensively and consistently demonstrates subject expertise, a business is essentially proving its credibility in the eyes of Google’s semantic search (Chapter 12). Amerland encourages companies to put faces to their work, (even though Google’s Authorship experiment is no more) because leveraging your employee’s expertise strengthens the overall value of your online identity. This has to do with what the author interchangeably calls influence, clout, or finding your true fans. Chapter 9 provides more guidance on working with internal and external influencers, as well as the difference between earned and owned media, however, the creator economy and the social media options have significantly changed since 2013. Treat the advice as a starting point for a deeper exploration into the topic of collaborations.

Semantic search rewards human-centric content #

If all roads lead to Rome, then all conversations about SEO lead to the topic of content.

“Content is key to everything. It has become the currency of the connected economy. The kind of content that you create now needs to be guided by a content creation strategy that operates within a specific framework of aims, targets, and intent.”

Content is the currency of semantic search, which is difficult to accumulate and easy to lose. In Chapter 6 dedicated entirely to content, David reinforces his position on being a responsible publisher that assigns value to content due to the latter being easily attributable to a person or a brand. That link between content and its author can either elevate or damage a brand's reputation. This is why content has to be collaborative and interlink; exist within the right context, and receive user validation through “social signals”. Alexander Bard, a Swedish writer and sociologist, illustrated this relationship with a simple equation: Reputation = Attention × Credibility.

A social signal is “a communicative or informative signal that, either directly or indirectly, conveys information about social actions, social interactions, social

emotions, social attitudes, and social relationships” (Poggi & D’Errico, 2010). In semantic search, a social signal is captured from the activity on social media, content shares, or user-generated content, which not only proves the level of engagement a piece of content receives but is also used to further refine the meaning behind content. According to Amerland, Google uses “social signals” to understand how people talk about content and in what linguistic constellations; assess the authority, trust, and context of the content; and improve indexing.

Understanding keywords and search intent #

In Chapter 1, David Amerland states, “Search is marketing”. This sentence reflects how much SEO has changed, spurred on by the rapid technological advancements at Google. In its early days, SEOs focused on making websites indexable. Nowadays, SEO is part of the content creation process that prepares content for semantic search.

This preparation entails understanding keywords, “the abstract representation of specific word sequences” (Amerland, 2013, p. 164). In the past, the rank of a website heavily depended on keyword frequency (or density), which led to webpages packed with repeated words and phrases that made for clunky text but improved search ranking. With the advent of the Semantic Web, content creators were encouraged to write freely in a natural language as Google’s search algorithm was capable of inferring meaning from synonyms and semantically related phrases, as well as the broader context.

It doesn’t mean that keywords lost their importance. As David already asserted in the previous chapters, by publishing on the web we are adding to the existing repository of content that has already been crawled and indexed by Google. We have to respect the existing connections, understand the meaning of words on the page and uncover the mental models of our target audience - specifically how they verbalise their intent online - for our content to reach them.

This work covers not only keyword research but also filling in metadata:

- Writing informative meta titles and descriptions that appeal to users when our content is displayed on the search engine result pages.

- Providing meta titles and descriptions for Facebook and Twitter previews, that respect the habits of content consumption on these platforms.

- Adding alt tags and captions to images, as well as selecting featured images.

Here, we should also pay attention to the type of rich snippets that we come across in our keyword research, as they signal to us the preferred format of content (an organization, a recipe, an event, or a product). Rich snippets are enhanced search results that appear on top of SERPs and can only be created through implementing structured data markup, such as Schema.org (Google, 2024b). Working with Schema (Schema, 2024) does require some technical knowledge, however, with certain web content management systems such as WordPress, it’s possible to purchase a plugin that suggests and generates appropriate Schema.

“The pre-Semantic Web delivered links that were present on search because of the keywords contained in the pages they represented. The Semantic Web delivers outright answers and pages that are directly associated with the question we have typed in search.”

Keywords go hand in hand with the searcher’s intent. Think about it the ice cream example earlier in this article. A person might be searching for the best ice cream in the city because they are craving ice cream or because they are searching for the best ice cream in the world. In these two examples, there is a clear and specific information need that the search engine will try to satisfy. This doesn’t just go back to personalisation but also to predicting.

For businesses, the commercial search intent (when someone is looking to make a purchase) is the most valuable. But providing guidance and nurturing authoritativeness in a topic domain goes even further towards creating a lasting content-fuelled relationship. Amerland asks the reader to consider the volume, velocity, variety, and veracity of data on the web before committing to the format, length, keywords, interlinking, metadata, and shareability of our content. Chapter 11 is a thorough exploration of what the 4 Vs of the semantic search mean for content creators.

“The secret to semantic search can be summarized in four words: volume, velocity, variety, and veracity. These are Big Data components, and semantic search is a Big Data manifestation. Unsurprisingly, it is governed by various combinations of these four Big Data components that hold as true for SEOs promoting a website as they do for a business or a brand promoting specific content.”

Where to go from here #

References #

Ahrefs. (2022). What is the Local Pack? Ahrefs SEO Glossary. https://ahrefs.com/seo/glossary/local-pack

Amazon Web Services, Inc. (2024). What is Interoperability? - Interoperability in Healthcare Explained - AWS. Amazon Web Services, Inc. https://aws.amazon.com/what-is/interoperability/

Amerland, D. (2010). David Amerland’s Website. https://davidamerland.com/#gsc.tab=0

Amerland, D. (2013). Google Semantic Search: Search Engine Optimization (SEO) Techniques That Get Your Company More Traffic, Increase Brand Impact, and Amplify Your Online Presence. https://www.amazon.de/David-Amerland/dp/0789751348/

Berners-Lee, T., Hendler, J., & Lassila, O. (2021). The Semantic Web: A New Form of Web Content that is Meaningful to Computers will Unleash a Revolution of New Possibilities. In O. Seneviratne & J. Hendler (Eds.), Linking the World’s Information (1st ed., pp. 91–103). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3591366.3591376

Better Content. (2020, July 6). Why the knowledge graph is important for content writing? Medium. https://medium.com/@better_content/why-the-knowledge-graph-is-important-for-content-writing-c53b5d3e7eb1

Edelman. (2024). 2024 Edelman Trust Barometer (p. 69). Edelman Trust Institute. https://www.edelman.com/trust/2024/trust-barometer

Fitzgerald, A. (2022). Domain Modeling for Structured Content [Andy Fitzgerald Consulting]. https://web.archive.org/web/20231130111619/https://www.andyfitzgeraldconsulting.com/writing/domain-modeling/

Google. (2024a). Creating Helpful, Reliable, People-First Content | Google Search Central | Documentation. Google for Developers. https://developers.google.com/search/docs/fundamentals/creating-helpful-content

Google. (2024b). Structured Data Markup that Google Search Supports | Google Search Central | Documentation. Google for Developers. https://developers.google.com/search/docs/appearance/structured-data/search-gallery

Halvorson, K. (2009). Content Strategy for the Web (1st edition). New Riders.

Kopp, O. (2022, September 29). What is semantic search: A deep dive into entity-based search. Search Engine Land. https://searchengineland.com/semantic-search-entity-based-search-388221

McConnel, C. (2023, December 13). Schema SEO Statistics 2024 2024-2023. KeyStar SEO Agency. https://www.keystaragency.com/schema-seo-statistics/

Poggi, I., & D’Errico, F. (2010). Cognitive modelling of human social signals. 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1145/1878116.1878124

Rudd, L. (2024, January 26). Why Google Authorship matters for SEO. No Brainer Agency. https://www.nobraineragency.com/seo/google-authorship-seo/

Schema. (2024). Schema.org—Schema.org. https://schema.org/

Search Engine Journal. (2023). Google Ranking Factors: Systems, Signals, and Page Experience. Search Engine Journal. https://www.searchenginejournal.com/ranking-factors/

Singhal, A. (2012, May 16). Introducing the Knowledge Graph: Things, not strings. Google. https://blog.google/products/search/introducing-knowledge-graph-things-not/

Statista. (2024). Global search engine market share 2024. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1381664/worldwide-all-devices-market-share-of-search-engines/

Steele, B. (2024, February 29). Entities & Ontologies: The Future Of SEO? Search Engine Journal. https://www.searchenginejournal.com/seo-trends/entities-ontologies-the-future-of-seo/

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). (2023). Tim Berners-Lee Biography by W3C. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). https://www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/

University of Washington. (2023). Steve Yegge’s Google Platforms Rant. University of Washington Computer Science & Engineering. https://courses.cs.washington.edu/courses/cse452/23wi/papers/yegge-platform-rant.html

Wikipedia. (2024). Semantics. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Semantics&oldid=1217530096

WordStream. (2009). What Is Black Hat SEO? WordStream. https://www.wordstream.com/black-hat-seo